November 21, 2020

In Conversation

James Ziegler talks about beginnings, influences and a new sculpture at kOAC

By Ricardo Castillo Argüello

Against the backdrop of his new creation, Shimmering Willow at the Kiyooka Ohe Arts Centre and Sculpture Park in Springbank, Alberta, artist James Ziegler speaks about his trajectory with Ricardo Castillo Argüello, KOAC’s Executive Director.

Starting with his earliest interest in art, geometry and mathematics and continuing up to his most recent tiny and large scale work, they discuss Ziegler’s influences, his practice in many different trades and as multifaceted innovator, artist, builder, and the idea of examining the world intuitively through three-dimensional forms as part of the human condition.

James Ziegler’s Shimmering Willow at the Kiyooka Ohe Arts Centre and Sculpture Park

Shimmering Willow, the newest addition to the Kiyooka Ohe Arts Centre’s sculpture park collection, is a wondrously simple, or simple-seeming, ingenuity. Standing at 7 plus feet high, the brushed stainless-steel piece by James Ziegler is at once playful and serious, marvellous and efficient, surprising and obvious. When seen from a distance in the middle of 10 acres of rolling hill prairie, its polished finish makes it appear as a solid mechanical conch or as a tepee-like folding web-and-sprit cone. Only when one gets up close is that a series of descending triangles cut from 3/16” stainless steel become apparent. They are gently curved like an inside-out umbrella, and bent backwards from the tip as angled shears that allow air to flow, making the sculpture move and shimmer with the wind and to cast shadows over the landscape.

Ziegler’s Shimmering Willow was commissioned by KOAC in December 2019 as part of the artist residency program, with support from the Peskisko Arts Fund at the Calgary Foundation, and funds from the Calgary Arts Development. Although the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted his 2020 Spring and Summer studio time, Ziegler finished his piece in late September . Ziegler is also collaborating with KOAC conducting his Ziegler Tiny Art workshops with students and adults. Working with KOAC, these are being adapted to the current COVID-19 times as interactive online workshops. People experience a hands-on transformation of paper patterns into 3D sculptures related to full- size works of art derived from similar patterns they work with.

It is hard to encase Ziegler’s practice and type of work, mostly because he has never been afraid to try new approaches or trades to enhance his inventiveness, even if they make him seem all over the place. A multifaceted creator, builder and maker of things, he was schooled in visual arts, painting, printmaking and sculpture at the University of Calgary and at the former Alberta College of Arts and Design (now Alberta University of the Arts). His professional curiosity leapt him into the world of architecture and home building, engineering models, 3D modelling, photo-realistic rendering, shadow studies, and digital graphics.

He is a skilled woodworker and craftsman and also an inspired inventor. His creations range from contoured foam back supports to his recently created new form of laser-cut paper art. In 1982, he invented a children’s construction toy system, ZAKS™, which was marketed worldwide by Irwin Toys, and sold in over 30 countries. The plastic modular toy construction systems earned him the Canada Award for Business Excellence, Gold Medal for Industrial Design in 1988.

We sat down with Ziegler to talk about his busy lifelong journey and how he now completed a circle by going full-time into his art practice.

Ricardo Castillo Argüello: Let’s talk about the very beginnings, of how art came to you, how it all began. Was it an epiphany or a gradual process?

James Ziegler: I was always interested in geometry. As a really young boy, I used to draw a lot of repeating triangles back in elementary school. When I was about 18, just starting university majoring in math and physics, I read “Utopia or Oblivion“ by Buckminster Fuller and became fascinated with his thinking about the potential of innovative design to create technology that does “more with less” and which improves human lives.

John Will and John Hall were also great influencers during that time of change for me. Stan Perrot, who was then the head of the Alberta College of Arts and a friend of the family, advised me to take a design course with John Hall. That was in 1972, and it changed me to the point of wanting to be a full-time fine arts student. My mother wasn’t very pleased. I ended up getting a BFA from the University of Calgary, but I attended both schools. In fact, that is how I met Katie (Ohe). She was part of a group of sculpture instructors at ACAD that I took courses with. At UofC, I ended up taking master-level classes in building science, like in architecture. At that time, those faculties were knocking Fuller’s geodesic dome around and some of his theories, which I was kind of immersed in.

RC: I read that his house ( he was the inventor of Geodesic Domes) was one of the first geodesic dome residences to be constructed. Fuller was a prolific thinker, no doubt, but more on the architectural and engineering side. How did that help in your development as an artist or sculptor?

JZ: I read about his invention of the Geodesic domes and the thinking behind it in his books on Synergetics. It inspired me to think more deeply about triangulated geometry. John Will recommended the faculty to invite Fuller to give us a talk. It was his turn to nominate someone and the faculty welcomed the suggestion. I bet there were a 1000 people out to see that Fuller lecture. We ended up having breakfast with Fuller at his hotel when John and I took him to the airport. His ideas really resonated with me, especially those about freedom for creativity and mastering as much knowledge and skills as possible to avoid specialization.

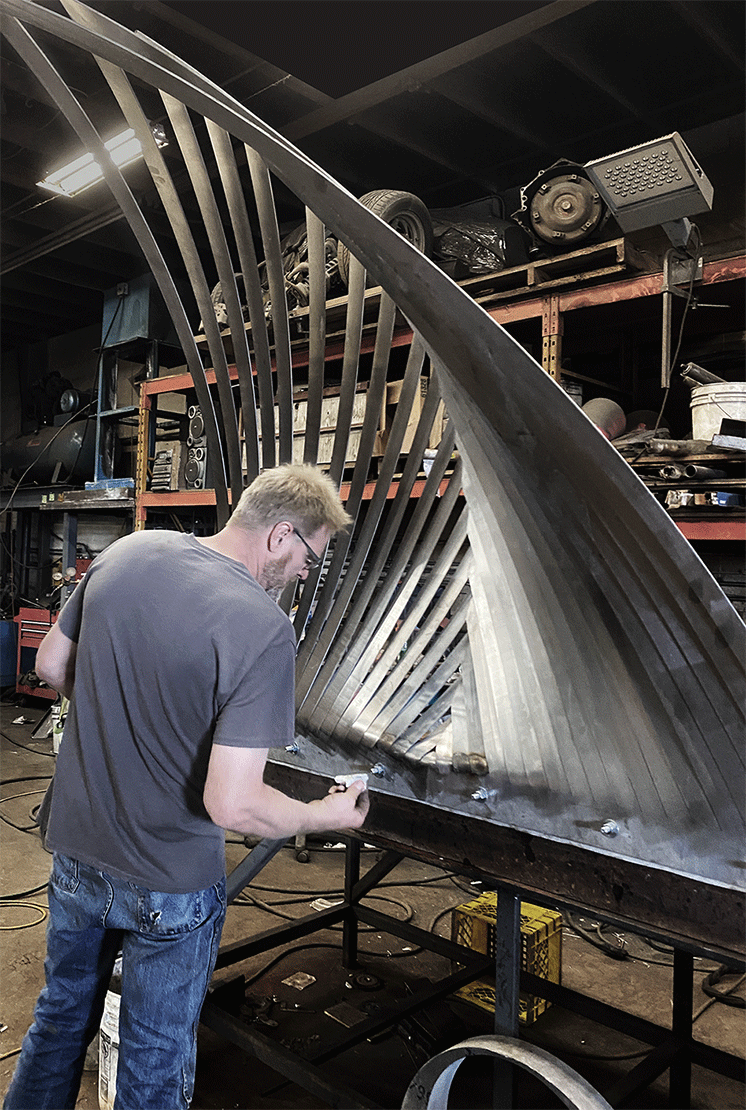

James Ziegler at the KOAC sculpture studio

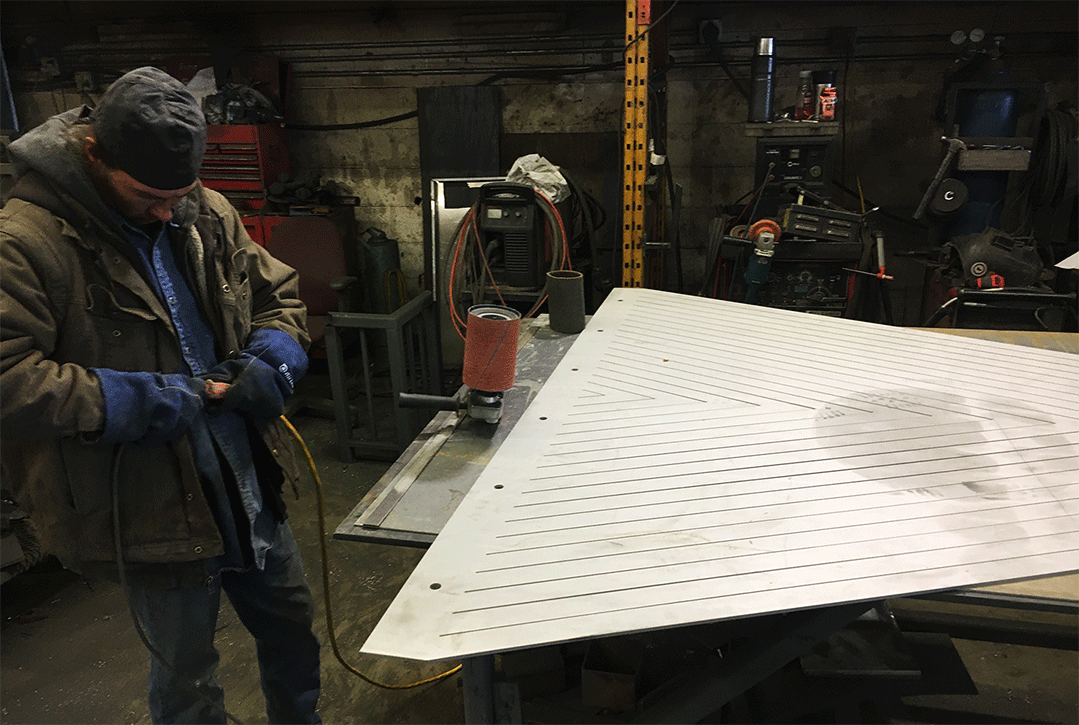

A master welder works on Shimmering Willow

During breakfast, I remember bringing up some of the criticism that was being thrown at him. Fuller looked at me in the eye and said sternly: “You can make an airplane out of spruce trees. It is not the material that you use. It is the intelligence with which you deploy it.” At another event when he was in Calgary years later, I showed him the prototype of my idea of (the toy systems) Zaks. That was before he died, and he said “I understand what you’re doing. Just continue, get on with it.”

1988 promo shot for Zaks Toys

Art can go in so many directions. When it comes to me, is about what are the senses telling us? How does it inspire us in more primordial ways, transcending that local cultural event?

RC: It is obvious, after working with you on KOAC’s programming and our interaction here, that there is a “Zeigler” quest to synthesize, channel, invent, craft, quickly and efficiently. What about the aesthetics, the other side of the equation, who or what is your influence there?

JZ: Just as with Fuller, I was deeply influenced by the work of Christopher Alexander. When you read or study his writings, such as in “The Nature of Order,” or even when he is talking mostly about architecture, it is in the way that his thoughts apply to sculptures that really get me.

Fuller was more about doing more with less, engineering with efficiency, and his notion that elegance will come out of that. While Alexandre came more from this organic process: what moved people for centuries, what’s the common denominator there regardless of culture, background, or what part of the world you are in, there are certain strengths that move us so that we feel complete, with a full sense of life with these things that we connect to.

Art can go in so many directions. Some of it is just so conceptual that it inspires people to think in different avenues. When it comes to me, is about what are the senses telling us? How does art move in our conscience? How does it inspire us in more primordial ways, transcending that local cultural event?

RC: Learning in art school is very important, but you seem to have acquired knowledge and skills from other trades that are critical components of what you create today. How much has your practice been a product of education? How much of finding new mediums or crafts?

JZ: I have continued to make art privately, paintings and sculptures throughout my career. My fallback to make a living was always building. I made studios for a lot of artists, for John and Joyce Hall, for example. That type of work paid a lot of my prototyping for Zaks. I made a living out of designing places for people. Another pivotal moment for me in my art journey was when Stan Perrot introduced me to Marion Nicholl. She needed this work done at her house. I built a large kitchen addition to her home with improvements that would make it easier for her and her disabilities from arthritis, including details for special cutting boards and drawers that she would be able to handle. Marion was spending most of her time in a chair.

Nonetheless, she took great delight in putting me through about 17 major revisions of this little addition. But I enjoyed it every time, very much, as she gave me a tutorial of why things were important this or that way, and how she would go in a tangent of the different aspects of design. That year she was awarded the Order of Canada. She is a continued inspiration to this day.

Art appreciation at the trades

RC: When I try to describe your background, it is hard to box you. How do you describe your type of work? Katie Ohe says you are a digital artist who expresses himself in analog, a scientist with excellent knowledge of material and complex engineering mechanisms and materials’ behaviours.

JZ: Well, I have experience in architectural design, home building, space planning, and at some point, I won an award in industrial design, so I must have done something right. I would like to think that the combination of sciences, math and physics, and computer skills, all merged with art, has given me some margin of flexibility. I’ve enjoyed, for example, supervising a team of architects to design site layouts and attraction buildings and theatres with 2D and 3D CADD for a magical theme park in Holland, planned by Doug Henning. I did that for three years, and it was a great experience. I did 3D imaging services for commercial developments and 3D modelling services for visual impact assessments used by land developers, engineers, architects and landscape architects. And I am very fond of my experience as volunteer President of the Joshua Creek Art Centre in Oakville, Ontario, where I converted an 1823 timber barn into an art gallery and designed its site layouts.

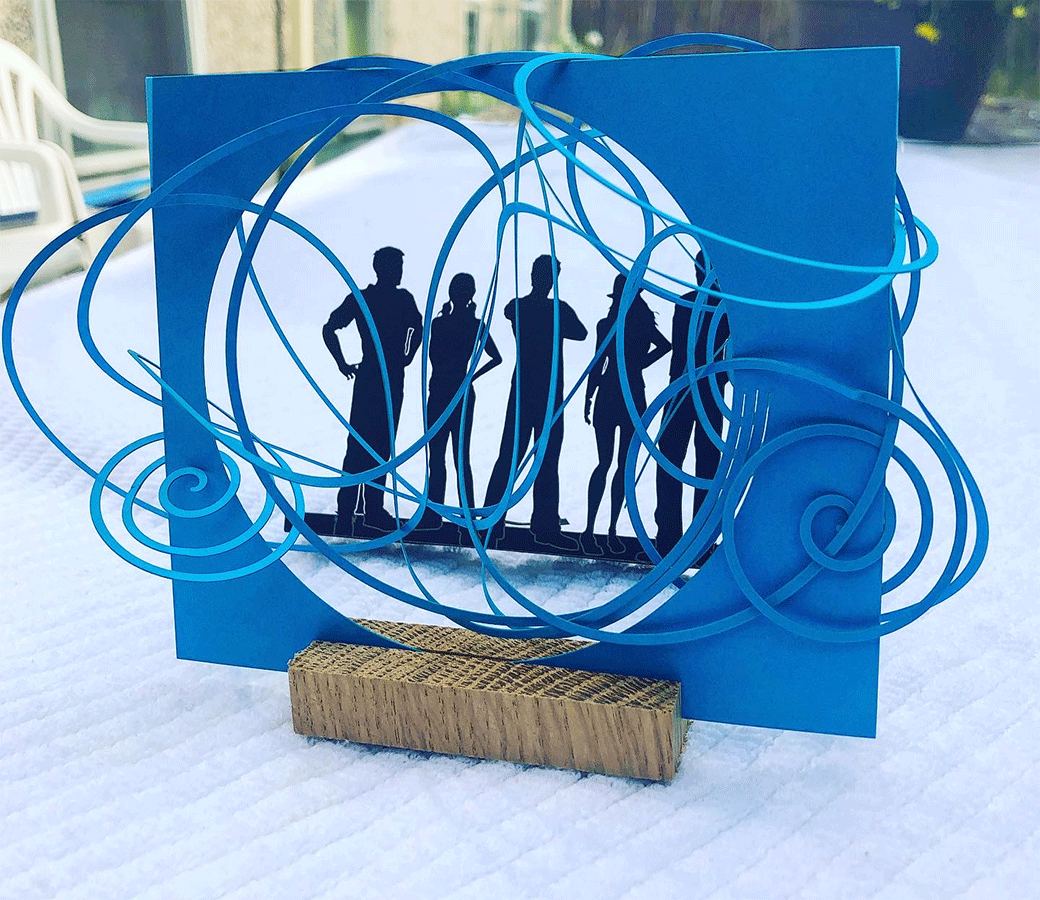

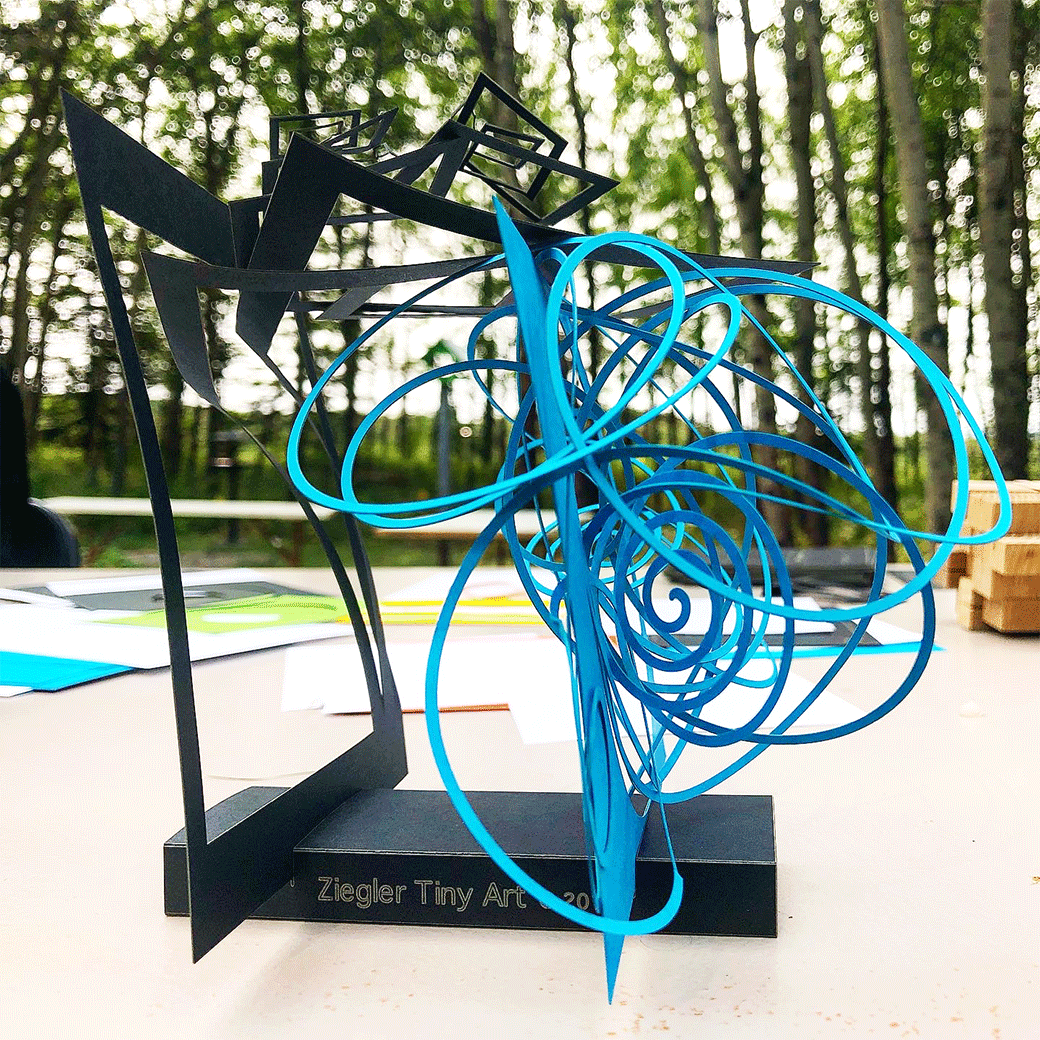

I think it was the ability to adapt my visual training to computer graphics precision that opened a new way of thinking for me. In 2019, I committed to working full time on my sculptures. When I came up with this laser cut paper modelling system, I realized I could create laser cut paper art to explore modern art. They became what I call Ziegler Tiny Art.

RC: And how is that tied to your making large-scale sculptures at this point of your life?

JZ: I am very grateful to Katie (Ohe). Since I moved back to Calgary and committed to making art, such as sculptures out of my tiny craft, I had not made much progress. I have spent a good part of my life making contracts (such as the viewshed and shadow studies, terrain analysis, used for site design and project proposals), and art was just something I was doing on the side. But when I showed these pieces to Katie, she said, this time you need to commit. That was a tall order. That was last year.

RC: So, Katie had a pivotal effect?

JZ: Yes, I see this as my third life. Katie had actually seen my Zaks toys when they were in the beginning stages. I remember how their movement really inspired her. It was much before they went to market. So, it was some good serendipity when last year a meeting I had got cancelled. And that morning, (sculptor) Neil Liske, a good friend of her and my next-door neighbour, told me he was going out to see Katie. I thought it would be a good idea to bring some of the pieces I was working on to ask her what she thought. We ended up spending like three hours going over these pieces. Her validation of what I was feeling about these pieces was very important to me.

The Shimmering Willow came out of that conversation. I said to her I wanted to do one in steel, and she asked, which is the one you would like to make? I showed her the tiny art version of the triangular figure, and she really liked it, and I commenced the preparatory work to make it. The first drawings I made were in 2019.

I saw a genuine engagement with this process when I shared the paper models with people who are not typically working in the arts or trained to appreciate creative experiences

Ziegler Tiny Art in perspective

Ziegler with students visiting the real thing

A Tiny Art iteration during an outdoor workshop

RC: Your piece is deceivingly simple. Not very many people know about all the calculations and technical considerations that it entailed. Tell us a little bit about the production process.

JZ: I had to put together a supportive team of trades and specialists to produce it, from laser cutting work, welding, metal fabricators, mechanical engineer, and suppliers of materials and polishing equipment. Then we worked with the KOAC landscape architect for the sculpture park and volunteers to assist in the installation. The entire form was sandwiched between larger metal and roll plates to create the arc over the triangle. After this process, each pair of tines are bent at the base. This is done to open the sculpture somewhat like a curved fan. The piece is intended to flex and vibrate with the wind. To adjust the range of movement, we need secondary supporting leaves fastened at the base. This is like leaf spring in a vehicle, adding support to the longer tines and enabling the tuning of the sculpture’s movement.

I saw a genuine engagement with this process when I shared the paper models with people who are not typically working in the arts or trained to appreciate creative experiences. But all of them, the welders, laser cutting teams and metal fabricators, became very supportive in a personal way from the beginning as soon as they handled the small models. In this way, from the initial stages, I see how what I do reaches out into the community and changes how others experience art.

RC: I remember Shimmering Willow a year ago in a paper model form. When we shared it with people to introduce the tiny art workshops in schools and out here at the Centre, we also said we were introducing the future sculpture and were giving them a hands-on experience of its form. How do you think they will react now that the actual piece is installed?

JZ: My art has two aspects: creating a permanent physical sculpture is one. The other engages people of all ages to discover their own creative moment from playing with smaller patterns that my sculptures are derived from. The virtual art workshops with KOAC are themed as Play, Discover and Create with that purpose in mind.

The patterns that I cut have innumerable configuration and variations. It is a process of play, discovery, observation and creation. I invite people to transform the pieces into 3D shapes and notice what it feels like to see the new forms emerge. The linear patterns that I create intrinsically will generate artistic outcomes as they are reconfigured. Repeating paths, echoing shapes cause both positive and negative spaces that are implicit in the pieces. It’s important that people see the relevance of these small pieces relating to larger art pieces. It connects their individual experience and validates what they and others have shared with a broader understanding of sculpture forms.

RC: I read an expression from Buckminster Fuller that said: “If you want to teach people a new way of thinking, don’t bother trying to teach them. Instead, give them a tool, the use of which will lead to new ways of thinking.” That sort of defines the Ziegler Tiny Art workshops, but it would also apply to your toys.

JZ: I found another expression of Fuller who said if we don’t understand triangulated geometry, we are doomed. I want kids to understand triangulated geometry and that examining the world intuitively through a three-dimensional form is a fundamental human pursuit. It is not just building a mass. We are so used to the Lego culture, in which we make Mass by default of only by the volume forming from the 3d object’s occupied space. That is to work as a default of Mass. Whereas to think in 3d really is thinking sculpturally. Meaning what is up or what’s down is irrelevant. It is what is going out and around what matters; the formed angles, which is what happens when you are thinking sculpturally. It is about working in all directions, not in just one direction or in a Cartesian Grid. That’s not the way Nature works or the way that 3D works.

The patterns that I cut have innumerable configuration and variations. It is a process of play, discovery, observation and creation for people to see how these small pieces relate to larger art pieces.

The idea is to get them to develop that intuitive sense, and we cannot just do that by coming to them from something cognitively. It all starts with the experiential reference, and from that point, we can then use our intelligence to put down solutions.

All these modular toys are really all about empowering people to play with the form, which is, in a way, a form of instant art because, as soon as you pull it open, you get a result. But what is more important is that it is you who is seeing it. It is you who is experiencing it, and that opens a foundation of confidence, and with the workshops, we are reinforcing that you are the creative spirit, and you can manipulate these tools that were given to you. And that you can do that with anything. But it’s drawing you out of your head, sensing, seeing, observing and then working with your hands and your tools: heart and mind.

RC: Katie (Ohe) said with these workshops and models, you could be changing how public art can be done. Part of that was about the idea that public art would not be just that fixed piece, but like we are doing now with the workshops, many people are playing with the same components, and all stakeholders are some experiential connection to what this piece will become.

But to end, let me ask you: what if a purist critic would say that by you using the computer, you are steering away from the wholesome artistic process of development. What about the notion that when you make something, a painting, or a sculpture, you cannot reproduce it again, but you can repeat patterns when you use your laser design?

JZ: What I enjoyed the most in the workshops with KOAC is that every time that we pull out the same patterns and figures and people manipulate them, I continually see something I never saw before. You start with a relatively simple pattern in a way. That is the root of your conceptual work. We are saying that every design you make today in this workshop starts with a geometric orientation, a conversation that is never the same.

To suggest that the way I conceive my forms might not be art would be as if saying that someone picking up the flute and not using her voice is not art. I use the computer so much that I can draw with the pen or the tools on the computer and I don’t have to think about it. It is just a tool. Whether it is a carving tool or a machine tool, the computer is no longer a machine when you transcend the point you are no longer thinking about. I started out with manual drawings for technical drawings, and I had to do a lot of graphic work. I have developed the skillset to pick up the drawing and translate it for the computer to do the drawing. That comes from my other trades as a builder and as a designer of toys. It is a combination of the essential tools from math school and the knowledge from art school about composition, line, drawing, character and all of that. Which was applicable in my work in different trades. But the most critical tool is the eyes. You are learning to see. How many of the people who go through art school are actively engaged in producing art? It may be a very small number if the answer is about how many are actively involved in using their sensibilities for how their eyes and senses perceive balance, order, and sequence to do things. Hopefully, a lot of them. Because that is what makes the difference.

Your generosity is more important than ever

The Kiyooka Ohe Arts Centre is a place for art and artists, for the curious, for the novice and for the expert alike – everyone is welcome to visit, to make, to learn and to talk about contemporary art, whether by traversing our sculpture grounds and gardens, or visiting (when appropriate) with our artists in studio or via our digital forums and workshops.

Regular support from our friends enable us to sustain our work with artists, audiences and communities. Help us keep our grounds open as an escape into Art-in-Nature during this unprecedented time.

Become a member. You can make a difference today. All memberships and donations receive a CRA donation tax receipt.

The KO Arts Centre Society of Calgary is a registered charity. CRA Business Account # 83391 4955 RR001.